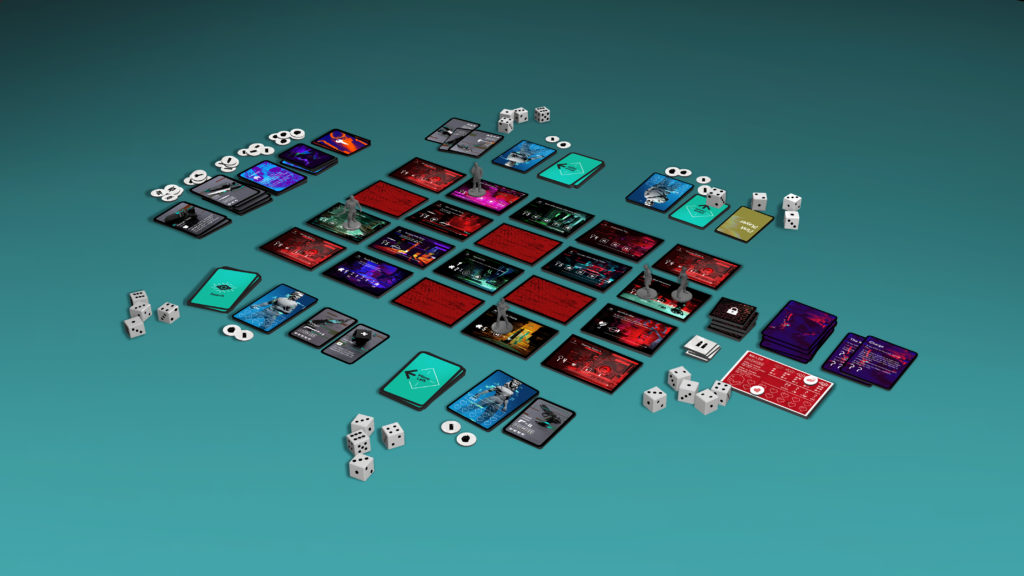

Halls of Horror Board Game: Game Development and Inspirations Part 1

Halls of Horror started out as a paper prototype for a video game. From there, it took two divergent, but closely knit paths towards becoming a better experience in the online multiplayer space and the tabletop. Join the game’s designer, Krzysztof Zięba, for a journey through the game’s development and how we got to where we are now.

In April 2018 I have started the development of a game that our company pitched to Microsoft’s Mixer as a kind of PVP choose-your-own-adventure game, in the vein of then-popular Mixer-exclusive Death’s Door: Aftermath. The first question was the scope – we had to decide on a game that would be very replayable, with many interactions coming from characters having to fight in an environment where there is only one winner. Being a fan of board games (not to mention an author of one published title in that space), my intuition told me that maybe using a tabletop-focused approach to the design could be a good starting-off point. Turns out that was a well-made first step.

Those first few playthroughs of a very rough, very much improvised prototype proved helpful in establishing two basic facts: that the core idea for the experience is solid and fun even in its unpolished state, and that it’s a good point from which we could start implementing things in the engine. At the same time, I took nothing for granted, and in those early two months of design me and the programming team were ready to turn on a dime if need be. Fortunately, the basic framework worked almost from the get-go: the game would involve characters moving around a grid, with RPG-like rollable tables for the results of searching, and the game’s basic goal and main antagonist – the Killer – provide enough fun to serve as a foundation for expanding the gameplay in interesting ways.

The character of the Master of the Ceremony was present in that first prototype with me playing the role similar to how a Game Master in a pencil-and-paper role-playing game, or a dungeon Overlord in board games such as Heroquest or Descent. The MC was in charge of keeping the game’s flow, and since this was a prototype for a video game, we also used a mechanic by which players would all use obscuring screens to make their movement in secret, and it was up to the MC to keep track of when two characters meet. Needless to say, it was a pain and I quickly realized that for the role of the MC to be fun, this mechanic would have to change significantly.

Secret movement in general is kind of a problem to implement in a board game. What’s very easy in the digital version would probably be more trouble than it’s worth in the physical world – there are only a handful of board games that successfully use this kind of movement, and even then most of them only do it for some players, but not all of them. This was the first tough, but ultimately right, decision that marked a crucial departure from the way the video game version of Halls of Horror did things. Instead of hidden movement, players could now see themselves on the board at all times. This made the tabletop version’s atmosphere much different, but – in my opinion – better suited to the PVP format and competitive character of a board game. Ultimately, even in a multiplayer video game you can sometimes have a match that feels like you’re alone and competing against the game’s systems, not other players – and still have fun – but it’s not what you’re necessarily looking for in a board game.

Other changes? While searching the rooms in the video game works roughly the same as it did in that early prototype (with a table of possible results and a single “roll of a die”), I quickly realized that trying to adapt the same way of doing things to the board game would feel artificial at best, and just unpleasantly jarring at worst. It just wasn’t a great fit, and felt less like a modern board game, and more like a weird multiplayer solitaire / light-RPG hybrid. That method would also ideally involve an MC to provide players with narration and act as the one consulting the dice roll with an actual result hidden from the acting player’s eyes. By that time, however, I already knew that we probably wouldn’t have an MC acting in this capacity – each player would have to resolve their Searches by themselves.

“When in doubt, use a deck of cards”. I don’t think that’s an actual motto, but a few more published board games and I might actually make it mine! When my previous title, In the Name of Odin, was stuck with a poorly working mechanic, I tried out cards as the cure, and it worked very well. Halls of Horror proved to be similar in this case, and so a deck of cards came to the rescue once again, introducing a more predictable and more board-game appropriate mechanic – drawing cards and looking for symbols matching your current location to check which reward you get. We’ll get into more detail on how this process works next time, but what’s important to note here is that, besides players seeing their movement around the board, this mechanic is probably the biggest diversion from the digital version of the game.

The key takeaway from the first few months of working on Halls of Horror as a physical tabletop game (and from the rest of its development, as you will read in the future) is that video games and board games might have a lot in common, but often differ substantially in their implementation of the same ideas. To make HoH something people could enjoy around a table, I had to make it increasingly LESS LIKE the original design it was adapting. Even though the two are much different beasts now, I think it’s clear at a glance that they convey roughly the same experience and in this way, the board game is a very faithful adaptation – without being blindly subservient to how the digital version plays.

Next time, I’ll cover some other aspects of Halls of Horror like the combat, how the ongoing design of the video game informed the board game’s mechanics (and vice versa!), and more big changes that made HoH the experience it is now.